The (patented) invention that changed the ski world

Skis are ancient inventions: they've been used in cold climates since we first figured out how to tie bark to our feet to move over deep snowpacks. But our modern idea of skiing as a sport emerged in the late 19th Century. For example, slalom was first raced in 1905, in Sweden.

If you ever have skied at least once in your life, you know that turning is the essence of skiing: without it, your first run will certainly be your last. Turning is more than just the way you change directions. It’s an art, it's a rebellion against the laws of physics, and it’s a reflection of your style. No two skiers will make the same set of turns down the mountain.

Skis themselves are the subjects of huge amounts of engineering these days. But contemporary skis were pioneered by Elan, which invented the "deep sidecut" ski (aka parabolic skis) and patented several designs in the late 1980s.

Sidecut – the subtle hourglass shape of the ski – goes back to skiing's prehistory. It was invented by now-forgotten artisans sometime before 1808 and was adopted universally after being popularized by Sondre Norheim and his friends in Telemark, Norway, around 1856. Early skiers, who carved their own skis, found that pinching in the waist of the ski made it easier to turn.

Since that time, the “straight” ski with parallel edges has been a rarity, enjoying real popularity only as a light cross-country ski for use in modern machine-set tracks, and for modern jumping skis. In alpine skis, sidecut shape has grown gradually deeper over the decades.

But the real revolution came from Jurij Franko and Pavel Skofic. Jurij Franko (often confused with his schoolmate Jure Franko, whose successful World Cup career was topped by a silver medal in Giant Slalom at the Sarajevo Olympics in 1984) graduated from the University of Ljubljana in 1983, with a degree in engineering, and joined Elan in 1987 as a lab manager.

In 1988, he had an idea for a deep sidecut ski, and his colleague Pavel Skofic calculated a suitable flex pattern. They organized a project called SCX (SideCut eXtreme, or eXperiment) and set out to build prototypes.

Franko's calculation was simple: “Choose the radius of the turn - 10 meters, for example. Choose the speed you want to ski - 5 meters per second for example. Calculate the centrifugal force and the lean angle, as for a bicycle. This is the angulation of the ski. Imagine a ski of constant width bent to the radius of the turn and penetrating through the snow. ‘Cut’ the ski with the snow surface, and there you are!”

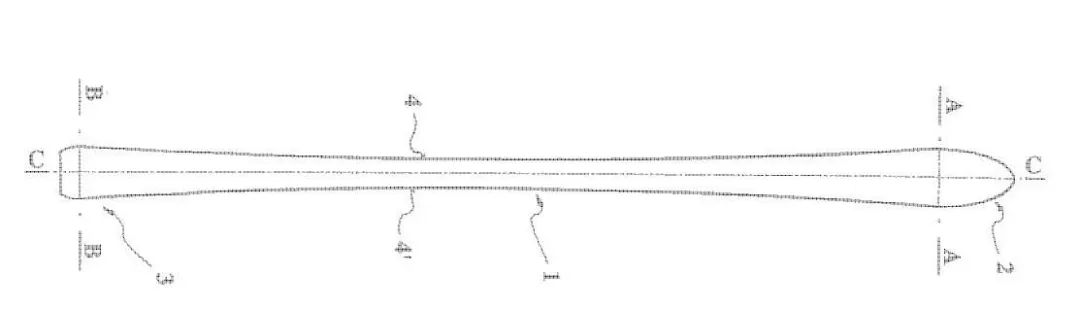

By 1991 Franko and Skofic finalized a 203cm mold for a Giant Slalom race ski with a 110-63-105mm profile – that’s a 22.25mm sidecut, three times what most racers were using for slalom at the time. Sidecut radius was just 15meters – about 35 percent of Jure Franko’s medal-winning Elans from 1984.

The SCX was incredibly fast on the Giant Slalom course. In its first local races, skiers on the SCX took eight of the top ten places. The new ski conformed more easily to the actual arc required to carve a clean turn in the race course. For any given turn, the racer needed less edge angle, and could therefore stand on a straighter, stronger leg.

One could doubt that such “simple” invention could be granted a patent.

In the examination process for determining the inventiveness, steps usually are summarized as followed:

1. Determining the scope and content of the prior art.

2. Ascertaining the difference between the prior art and the claims as well as the technical problem to be solved.

3. Considering whether the difference is non-obvious or anticipated related to prior arts.

The technical effect, particularly unexpected technical effect, is considered in the inventiveness step.

The prior art of this invention discloses the alpine ski with a front and a rear section which are wider than the main section, but there is technical problem related to current technology, i.e., the snow would have a jerky contact with the edges of the front and rear section rendering the ski unstable.

This invention provides the new ratio between the narrow middle section and the widest front section, and the new ratio between the narrow middle section and the widest rear section, in order to distribute the force generated at skiing.

So, the invention could be granted mainly based on following reasons:

1) the new ratio is not disclosed in prior arts and not anticipated in light of prior arts;

2) this ratio solves the above technical problem and yields good technical effect.

Franko and Skofic patented the SCX in 1994. The SCX is considered one of the most important inventions in the history of the ski.

*This article is part of a longer contribution published by HFG in 2019