Spinning, Pilates and Aspirin: beware of Genericization

If it's quite well known that sometimes it's difficult to obtain a trademark, it's less known instead that it is often even harder to keep it.

While some brands simply failed to register as trademarks at all, or in some cases weren't renewed or were abandoned, others have to fight constantly against “genericization” to maintain the trademark.

In fact, in our daily life we often use lot of terms probably without knowing that they are brand names, still protected by trademarks, so they can't be used (essentially by competitors or for commercial use) without possibly facing trademark infringement lawsuits.

However, since they are commonly used to indicate the generic products, they could be in danger of “genericide”.

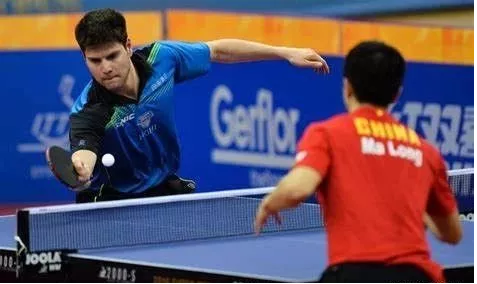

So, for now, you can play table tennis but not “Ping-Pong”: Ping-Pong is a federally registered trademark first developed by Parker Brothers, Inc. and now owned by Escalade Sports. The registered trademark Ping-Pong indicates a brand of equipment used to play the sport of tabletennis.

Velcro is one of those products where trying to describe it in other terms doesn't work easily even though it's trademarked: the trademark owner, Velcro Industries BV, asks that its products be called Velcro hook and loop fasteners or Velcro fabric fastening products.

Who wouldn't want a Jacuzzi in the bathroom? Jacuzzi is actually a corporation that manufactures whirlpool bath tubs and hot tubs. The company has held the trademark since it registered it back in 1978. Jacuzzi Brands has roots in the aircraft industry.

There's plenty of product like these: Band Aid, Xerox, Bubble Wrap, Lycra, Teflon, Vaseline, Super Heroes, Post-it, Rollerblade, Memory Stick, Lava lamp, Hula Hoop, Frisbee… How many of these words were you actually aware they're trademarks? And how long will they maintain the mark?

Under trademark law, a word cannot be a trademark if it is generic. For example, the word "bike" cannot be a trademark for a bicycle because the word is just a standard term for the type of product it represents.

Similarly, if a trademark becomes so familiar that it is generic, it can no longer be eligible for protection. When a mark becomes so common that it simply signifies the type of goods it represents, it has become generic and can no longer be protected by trademark.

If a company's trademark becomes generic, anyone can use it without fear of a claim of trademark infringement from the trademark owner. This is because the word or symbol no longer indicates to the public that the products or services bearing the trademark originate from one source, namely, the trademark owner.

Someone could think that this genericization is good both for consumers, who identify the product immediately, and for companies, who become very well-known thanks to those products.

Actually, from a consumer point of view, loss of a trademark denies the opportunity to identify preferred brands and repeat satisfactory purchases; from companies’point of view, it destroys the owner's investment in its valuable asset.

That's the reason why companies usually fight to maintain the trademarks and discourage people from using the mark in a generic way, pushing them instead to use the trademarks together with the common name or description of the product or service.

Back in 2012, a Czech company called Aerospinning Master Franchising applied with the European Union Intellectual Property Office to revoke the trademark for Spinning registered in 2000 by Los Angeles-based Mad Dogg Athletics.

Even though Mad Dogg contends that indoor cycling cannot be referred to as Spinning unless done without its specific bikes, the European Union Intellectual Property Office agreed with Aerospinning that the term had become a generic name for exercise training, no longer worthy of protection.

After the office deregistered the Spinning mark, Mad Dogg appealed to the European General Court in 2016.

That court ruled in 2018 that underlying ruling must be annulled because of an error of assessment that “vitiates the contested decision in its entirety.”

The error was that the trademark authorities focused on what the general population of the Czech Republic thinks about “spinning,” despite evidence that 95 percent of Mad Dogg's sales of indoor cycles went to gym operators, rehabilitation facilities or other professional customers.

Indeed because these cycles cost so much, the court agreed that “indoor cycles are rarely purchased by individuals.” And gym operators and professional customers, who are the relevant public for the equipment, recognized Spinning as a trademark.

For one who wins there's one who loses though.

Pilates, one of the hottest fitness trends in America, lost the trademark back in 2000. A decision in Manhattan's Federal Court declared that Pilates, like yoga and karate, is an exercise method and not a trademark. Since consumers identify the word ‘Pilates’ as a particular method of exercise, a company cannot monopolize it.

There's also the possibility that a trademark is cancelled in some countries and maintained in others.

That's, for instance, the case of Aspirin. Patented 120 years ago (on March 6, 1899) by Bayer, it is the most used drug against flu, colds and congestion symptoms. After World War I, Bayer lost the right to use its trademark in many countries. As part of the war damage compensation, specified in 1919 with the Treaty of Versailles following the German surrender, the name "aspirin" ceased to be a registered trademark in France, Russia, United Kingdom and the United States: it became a common name that could be written in lowercase letters.

There are few nations, though, including Italy and Canada, where the name of the drug is still a registered trademark.

For us, let's say that would be much easier to use a brand to indicate common products, but on the other hand, if we don't, we could for sure improve our vocabulary…

HFG Law&Intellectual Property