The importance of being (Ab)original

Images of Wanjina, shown here at Donkey Ridge in the north-western Kimberley region of WA, are characterised by halo-like headdresses, mouthless faces, and large, round eyes. (Image Grahame Walsh / courtesy Kimberley Foundation Australia)

Last year my attention was caught by a news story that hit the headlines.It was something regarding Aboriginal art (that means, art made by the indigenous people of Australia). It should be noted that Aboriginal art is considered sacred and has its symbolism, iconography and meticulous rules.

Furthermore, a non-indigenous Australian does not have the authority to paint an Aboriginal piece of artwork. It seems obvious, but Aboriginal art is only considered Aboriginal if painted by someone who is of that origin. The most famous style of Aboriginal art is the so-called Dot Painting, which originated from the time of white settlement when the indigenous people feared non-indigenous people could understand secret knowledge held by the Aboriginals. Double-dotting obscured any form of meaning but was still discernible to Aboriginals.

The “Australian Copyright Act 1968” protects the work and the author of Aboriginal art. As you probably know, copyright generally protects an artwork from being copied during the lifetime of an artist and for 50 to 90 years after death, depending on the Country’s legislation.In Australia, this limit is 50 years (cf. Australian Copyright Act 1968, sub part III, art. 33.2).

Nevertheless, for Aboriginal art this law has been disregarded for decades, as non-Aboriginal people assumed that, being Aboriginal art, they didn't had to ask anybody.

That said, as you can imagine the dot painting is quite common. That doesn’t mean every artist using dots is copying Aboriginal art. Just think about George Seurat and Paul Signac, who developed the Pointillism in 1886, or Yayoi Kusama, the Japanese artist who created the Polka Dots.

Nevertheless, in 2018 Damien Hirst has been accused of copying an Aboriginal artist in his series called Veil Paintings, where the British artist expressed in response that he’s been inspired by the French artist Pierre Bonnard and by the above mentioned Seurat.

"Damien Hirst: The Vell Paintings," installation view at Gagosian Beverly Hills. Artworks ©Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2018. Photo by Jeff McLane.

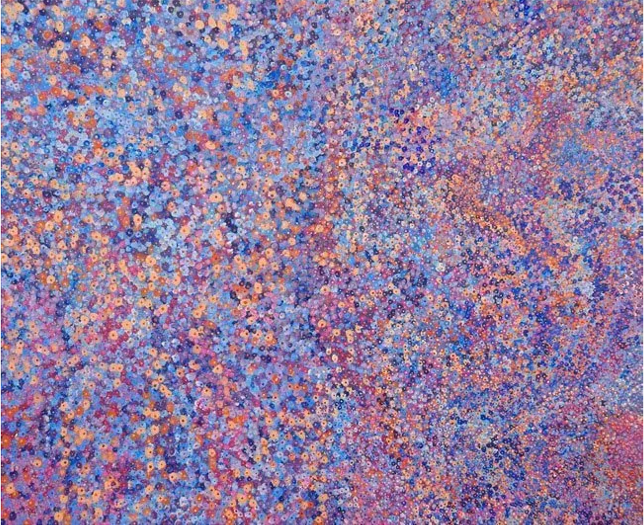

After being accused of copying the work of a famous Aboriginal artist, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, as well as other female artist from a specific desert area in Alice Spring, Australia, Hirst replied he was completely unaware of the Aboriginal work and artist.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Kame - Summer Awelye II (1991). Courtesy of Sotheby's London.

Kathy Maringka, Tjulpuntjulpunpa (2017). Courtesy of Olsen Gruin Gallery.

Can we believe him? Well, maybe yes, maybe not.But at least we should grant him the benefit of the doubt, whereas in other cases the forgery is evident, as in the case of the British TV Show called After Life, released by Netflix in 2019.

Ricky Gervais as Tony in Netflix series 'After Life' sitting in front of a fake Aboriginal artwork. (Netflix)

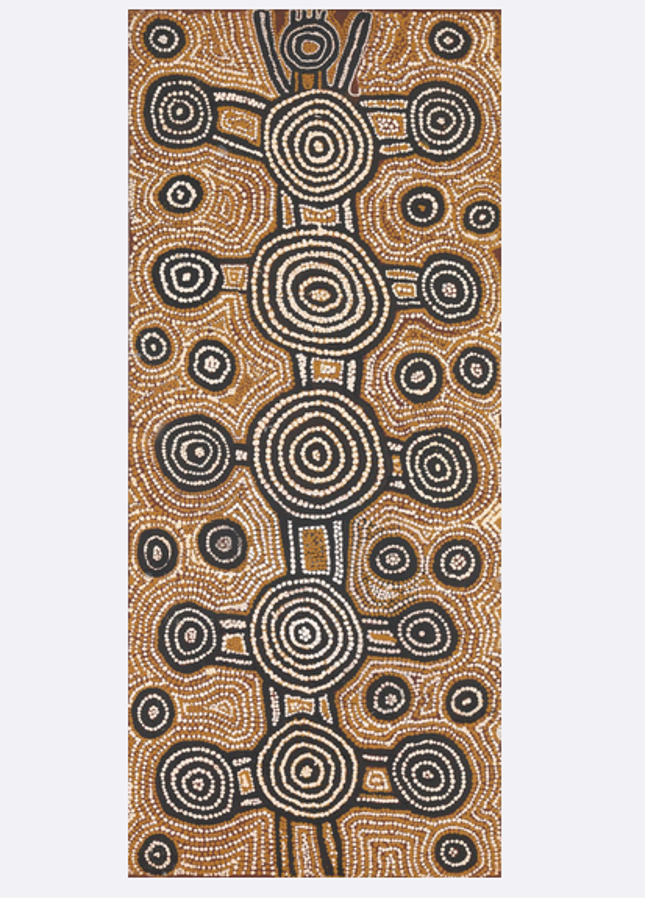

The set of this TV shows is a house plenty of ethnic souvenirs, and one of these is a big painting which turned out to be a copy of a famous work called 'Tingarri Dreaming' (well, famous for who’s inside the Aboriginal art) which is part of the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, in Melbourne.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of Ron and Nellie Castan, 1989 ©The Artist/Licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited

The entire Aboriginal art world was horrified by the “cultural theft” and started an action to raise awareness about the continuous misappropriation of the sacred indigenous art by people who don’t know the history and the culture of the country.

After some months, Richard Gervais, producer of the TV Show, agreed in paying compensation to the Aboriginal artist, Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, for using that unauthorized reproduction. Furthermore, he signed an agreement for the use of an authorized print of the same work in the second season of the Show.

So, everything ok, right? Well, yes, and no.

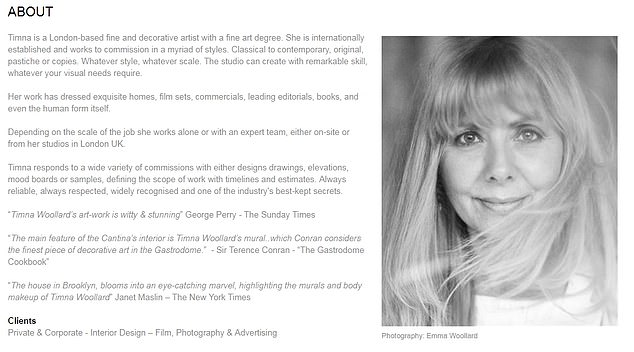

While I completely understand that Aboriginal art is sacred and not a 'style' or trend that can or should be replicated, and the copy of this kind of art is often perpetrated with little or no consequences, on the other side what caught my attention in that news is the fact that the artist, Timna Woollard, actually advertises her work on the web, explaining that she can reproduce any kind of style, “classical to contemporary, original, pastiche or copies” and that she dresses “exquisite homes, film sets, commercials, leading editorials, books”. Nobody is wondering that she is actually advertising she’s a forger.

Screenshot from Timna Woollard’s website

So, what about other minor artists eventually imitated or copied?

After being asked about the copy of that painting, Woollard replied she “was not as educated on the sensitivities around Indigenous art in the 1990s [when she did the copy] and would never make such a painting again” (reported by The Sydney Morning Herald, October 29, 2019).

The point is that copying an artist can have different meanings and different values. While is quite evident, if you hung up in your bedroom a very well know work by De Chirico, Matisse or Pollock, that it’s a copy, it’s not the same with less known artists. And this can address to them a quite big damage.

Furthermore, we have to keep in mind the legislation about the copyright, which (as said) protects the work and the artist during the entire life and from 50 to 90 years after the author’s death. It’s not the same, then, from a legal point of view, to make a copy of Rembrandt’s paintings or, let’s say, of Vettriano’s.

By the way, the “Tingarri Dreaming” copy, called by the forger “An Aboriginal Dot style painting”, has been removed from Woollard’s website, while other reproductions of more famous artists remain public. Between them, Lempicka (dead in 1980), De Chirico (1978), Matisse (1948) and many others.

HFG Law&Intellectual Property