Forgery in art business: from oil on canvas to water paint

Last month, July 10th, in a farm close to Detroit, Michigan, FBI discovered an art forgery factory. The forger, D.B Henkel, a 60 years old man who describes itself as an artist, is accused of producing fake paintings and selling them as original works of important American surrealist painters.

In the last 5 years, he supposedly painted at least 8 probable forged paintings, five of which were billed as previously unknown works of Ault, an American artist active through the 1940s. Two other paintings were purportedly created by Crawford, an artist active through the 1970s whose precisionist style was similar to that of Ault. The last painting was purportedly created by Abercrombie, a surrealist American artist active through the 1970s.

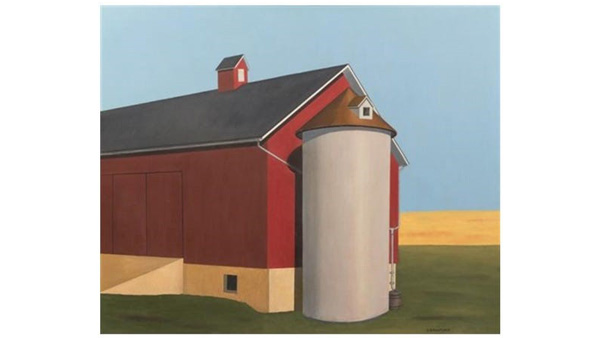

“Smith Silo” , purportedly by artist Ralston Crawford (Photo: Artnet)

D.B. Henkel received 670,000 US dollars from the selling of those works.

Art forgery also damages Chinese masters and here an incredible story that we have found.

In 2010 the Chinese art school curator at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Xiao Yuan, has plead guilty to charges of copying more than 140 paintings from Chinese masters. While working at the school he replaced the originals from the library's collection with fakes done by himself and sold the masterpieces at auction.

Xiao Yuan, as school curator who acted also as custodian of the works for two years, gained over 34 million yuan ($5.5 million). The stolen works included paintings by influential 20th century artists Qi Baishi, who used watercolors, and Zhang Daqian, who depicted landscapes and lotuses.

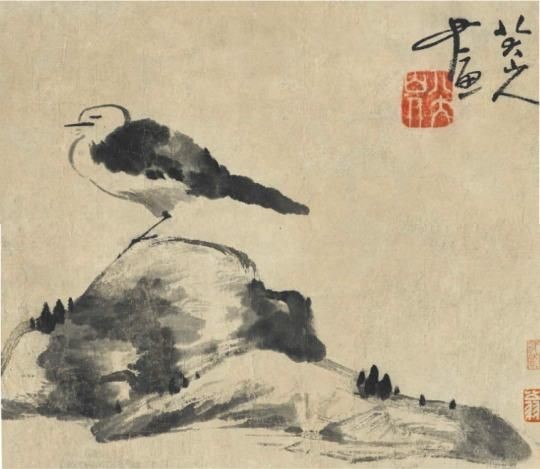

One of the painting copied by Xiao Yuan: Bird and Rock by Bada Shanren, 1626-1705. Credit: Christie’s

Nothing new under the sun, you might say. The point is that Xiao Yuan wasn’t alone. Xiao told to reporters that on his first day on the job he noticed fakes already hanging in the gallery.

Artist always needs inspiration. And there is more. Later on, after he replaced some of the remaining masters with his own fakes, he was surprised when he noticed that the fake paintings done by him to replace the master (sold at the auction) were substituted with even more fakes.

Well, the art of forgery is a profitable market: even though the technologies to discover the real nature of a piece of art are quite advanced, scientific examination is not so useful for contemporary works, and art collectors and galleries are often inclined to want some masterpieces for their collections and they want to believe that what they bought is original.

As a matter of fact, many forgeries are made to supply a precise demand of collectors or museums.

And this is not a recent phenomenon: in the first and second centuries AD, sculptors working in Rome made replicas of Grecian works to satisfy the demands for Grecian sculptures of the previous centuries, and sold them not as replicas but as booty from Greece.

So, even if some forgers make replicas, or art “in the style of” to gain recognition of their own ability or to deceive the critics, or to make a hoax with the intent of confounding the experts, anyway the main reason for fraudulence is money.

There are 3 kind of fraudulence in the art field, the most common of which is forgery: making a work and selling it with the intent to defraud by falsely attributing it to a priced artist.

Plagiarism is the false presentation of another’s work as one’s own: more used in literature and music, is difficult to prove, since the possibility of coincidence is always an option and the evidence of stealing must be proved.

Piracy is more often a business fraud than an artistic one: it frequently occurs with the reproduction of books, movies, music, without authorization and royalty payments to the author.

The fundamental consideration in determining forgery is the “intent to deceive”. Copying a work for study purpose, or doing it “in the style of”, is not considered itself a forgery, nor it is the restoration of a damaged painting, even if the restorer creates significant part of the work.

Misattributions may result either from honest errors in scholarship — as in the attribution of a work to a well-known artist when the work was in fact done by a painter in his workshop, a pupil, or a later follower — or from a deliberate fraud.

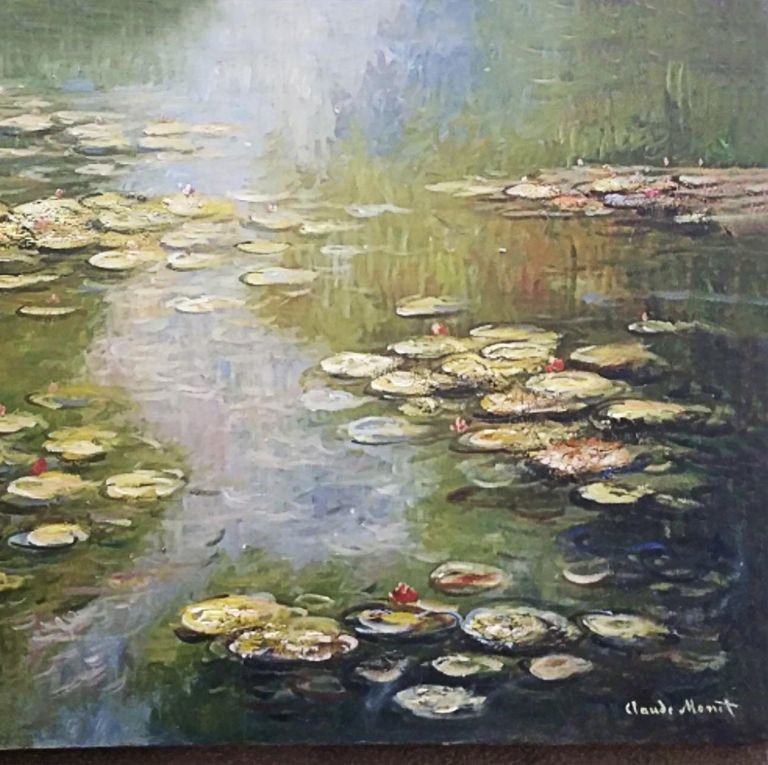

“Lily ponds” supposedly by Monet, forged by Tony Tetro (Photo: Town&Contry)

It happened often, even recently. In November last year Prince Charles was dragged in a scandal for displaying at Dumfries House, his mansion in Scotland, a series of masterpieces that turned out to be fakes: the works by Picasso, Dalì, Monet and Chagall were actually cheap imitations done by one of the greatest living forgers, Tony Tetro. So, after 3 years, the paintings were removed from the royal walls.

Controversial attribution has “The beautiful Princess”, previously known as either “Profile of a Young Fiancée”, and catalogued as German School, early 19th Century.

In 2008, based on forensic evidences, this work was attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci (with the quotation raising from 20,000 US dollars to more than 100 Million). But in 2015 a twist reopened the game.

One of the most skilled forgers on the planet, able to sell to great international museums Assyrian reliefs, Egyptian statuettes, paintings by Otto Dix, sculptures by Paul Gauguin and Henry Moore, declared himself as the author of the portrait.

“I took a 1587 parchment and drew it by rotating it 90 degrees to mimic Leonardo da Vinci's left-handed art” , Shaun Greenhalgh writes simply in his autobiography. Experts refuse this statement, and require proofs of the forgery.

“The beautiful Princess”, attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci (Photo: Palazzo ducale Urbino)

We might do here some considerations about aesthetics: what is the real difference in value a work of art that has been on display for years, after it has been proved to be false?

As James Stunt, the man behind the rip-off against Prince Charles, said to USA Today: “Let’s say they [the paintings] were fake. What is the crime of lending them to a stately home, to the Prince of Wales and putting them on display for the public to enjoy?”.

This is somehow a philosophical point: the object itself has not changed, only our opinion of it did. The monetary value has been reduced from that of a rare, expensive, original masterpiece to that of a good but fake imitation. However, as per the aesthetic point of view, it is a perversion of the truth.

“The forgery presents a false understanding of the work of an artist or an ancient culture, one which has been perverted in its modern translation. To appreciate the work of ancient artists their work must be studied alone and not be diverted by forgeries, or one will be inexorably misguided. The element of risk can be minimized but not eliminated. […] In order to acquire great pieces, particularly from newly discovered and relatively unknown cultures, it is necessary to take a calculated chance.” (Joseph Veach Noble)

The collector who has never bought a forgery probably has never bought a great piece of art.

HFG Law&Intellectual Property