Coexistence of similar Trademarks: How is it possible?

The numbers of trademark applications in China are huge. In 2020 alone, there are more than ten million trademarks filed at the trademark office. [1] Until 2021, the number of valid trademark registrations in China is 37.24 million. [2]

With such an enormous volume of trademark applications and registrations, it becomes quite normal that trademark applicants have encountered rejections due to prior existing trademarks. When being rejected, a letter of consent (LoC) sometimes can be the way to still ensure a successful registration of the mark.

In practice, however, achieving a LoC and having it admitted by the CNIPA could be complicated. Unlike the UK[3] or some other jurisdictions, the PRC Trademark Law does not include regulations about the admissibility of a LoC. Nevertheless, relevant authorities might accept a LoC in some circumstances, provided the counterparty is willing to sign a LoC and the co-exist of trademark will not cause confusion among relevant consumers.

What do the authorities look at?

When considering whether to accept a LoC, the CNIPA and the Court generally consider two factors. The first factor is that the two trademarks should have certain differences. For example, in the below case of BREAL/BOREAL, the TRAB decided to accept a LoC submitted during an appeal against refusal because there are some differences between trademarks in disputes.

| Applied trademark | Cited trademark |

|

|

|

The second factor is that the co-existence of the trademarks should not confuse relevant consumers. For example, in the UGG/UCG case, the Court held that the disputed trademark’s designated services, besides import and export agency, are not similar to the designated services of the cited mark. The LoC manifests the cited trademark owner’s disposition of its trademark rights and should be respected in the absence of evidence that the consent of co-exist would be detrimental to the interests of consumers.

| Disputed trademark | Cited trademark |

|

|

When considering the strategy of using a LoC to settle disputes, it is important to bear in mind that the letter alone does not suffice; possible confusion among relevant consumers also matters. This is to say that despite both parties’ intention to co-exist on the same or similar products, the Court will also protect the interests of consumers.

No letter of consent for TAYRON/TYRON

In the 2021 TAYRON/TYRON-case, although the trademark applicant has submitted a co-existence agreement, both the CNIPA and the court decided not to accept the LoC.

| Disputed trademark | Cited trademark |

| |

|

The court held that the designated goods of the disputed trademark and cited trademark belong to the same subclass, and thus they constitute similar goods. The difference between the disputed trademark and the cited trademark is only one Latin letter. If the disputed trademark and the cited trademark are used together on the same or similar goods, consumers will likely to believe that the goods bear the trademark come from the same owner or have a specific relationship between the providers of goods, thus leading to confusion and misunderstanding.

Although in the decision the Court has not mentioned the trademark owner’s business areas, it is possible that the trademark owner’s main business have been considered by the court because the trademark application is in the automobile industry and the owner of the cited trademark is in the tires industry. The co-existence of the two trademarks might cause confusion among relevant consumers because tires are used on automobiles.

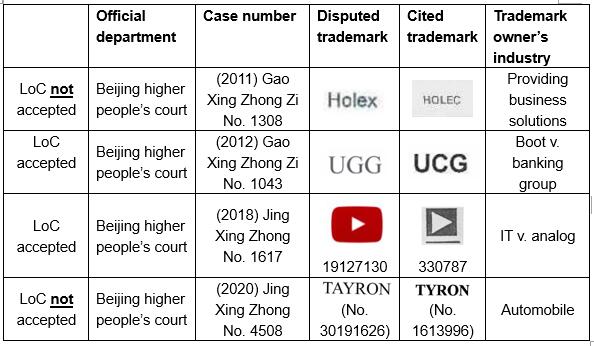

A similar pattern can be found in the Beijing higher people’s court’s decisions and relevant authorities’ documents. It can be seen from below examples that when the trademark owners of the cited trademark and applied trademark are in different industry, the LoC have a higher chance of being accepted by the Court. Additionally, relevant authorities’ documents also show that the possibility of confusion is essential to protect the interests of consumers.[4]

Dead or alive?

In conclusion, even if a consent is legal, authentic and effective, it should also exclude the possibility of confusion and misunderstanding of the source of goods, and then relevant authorities may accept it. Sometimes a LoC can be a useful tool for overcoming a trademark refusal and settling potential infringement, and sometimes it is just not practical to reach a LoC and have it accepted by authorities. Naturally, appeals at courts could also make a difference in the result.

For now, the Letter of Consent is still alive in China, but needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.