Can the artists use a brand without permission?

Ye HongXing, Isolate, 2020 (Courtesy of Art+ Shanghai Gallery)

Recently, I’ve been invited to a concert at the Art+ Shanghai Gallery. While the musician was playing, I was admiring the piece of art on the wall behind him, an interesting collage of images, painting and small stickers, work by Ye Hongxing.

What caught my attention in the painting was the presence, here and there, of famous fashion brand names, logos and products, such as Gucci, Moschino, Fendi, Kenzo, Nike, Converse. Looking more carefully, I could recognize, between others, images of Kaws’ Companion toys, The Beatles, a kind of pop version of The girl with the pearl earring, Champion’s caps, and the phrase “Arbeit macht frei” as it appears on the gate of the Dachau camp.

So, after the concert ended, I found myself thinking about what happens if an artist uses unauthorized images or brands in his/her artistic creation.

|

|

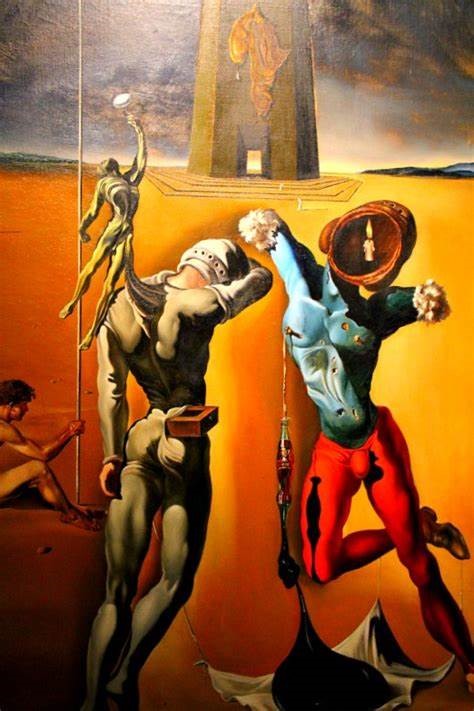

The first case that hit my mind was of course Campbell’s Tomato Soup by Andy Warhol, which is maybe the most famous brand in the history of modern art (even if not the first one: several years before, in fact, Salvador Dalì painted a Coca Cola bottle in his Poetry of America, in 1943). When Warhol painted the tomato soup in 1962, Campbell considered the possibility of suing the artist. But the marketing manager, who was clearly quite smart, decided to play with it instead, and sent to Warhol some of Campbell’s soup cans: “I have learned that you like Tomato Soup so I am taking the liberty of having a couple cases of our Tomato Soup delivered to you”. That was a great move. After a while, the company also asked Warhol to make a paint as a gift for a retiring board manager, paying for it 2,000 dollars. Now Campbell is probably the most well-known tomato soup in the world. |

Salvador Dali’, The Poetry of America, 1943

Shortly after 1962, also Mario Schifano began appropriating corporate logos in his works, particularly those of Esso and Coca-Cola.

Mario Schifano, Esso– Coca cola (tutto), 1962

Warhol also used commercial brands as his source material in a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, where the Dove of the soap flies over the Christ’s head (as the Holy Spirit) and the logo of the General Electrics appears on the side (as the source of light, which is the favorite way to evoke the presence of the God Father).

Warhol, Last Supper, 1986

Talking about Last Supper, another artist used commercial brands in her interpretation of Leonardo’s masterpiece: Tomoko Nagao.

The art piece reads back in a Pop and contemporary key, in which Jesus and the Apostles eat a junk food dinner on a table laid with an Ikea cloth (which is signed by the artist) together with other well-known pop icons, like Lady Gaga.

T. Nagao, Leonardo da Vinci The Last Supper with MC, Easyjet, Coca Cola, Nutella, Esselunga, IKEA, Google and Lady Gaga, 2014

Spot the brand! Trying to find all the brands mentioned in the title can be a good exercise.

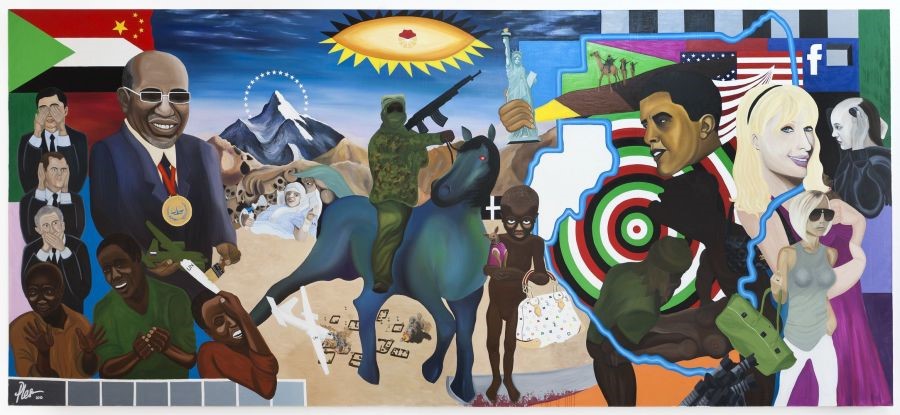

When famous artists use logos, it can be taken as a sort of tribute to the brand. That’s not the case of Darfurnica, a work by Nadia Plesner, one of the most discussed pieces using an iconic brand. The painting represents the war in Darfur, clearly recalling – not only in the name - the Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica.

The artist, touched by the dramatic conditions of the civil population in Darfur, wanted to raise awareness in the public opinion: we are often more interested in the news about fashion business than in the news about humanitarian emergencies, physically and mentally distant from us.

She then depicted, in 2011, a huge painting (32 squared meters), where an African naked boy is holding the Luis Vuitton’s iconic bag Audra (which by the way is designed by Japanese artist Takashi Murakami) and a dog dressed in pink, obvious reference to Paris Hilton, which is also portraited in the painting, as well as other famous figures like Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Victoria Beckham.

Nadia Plesner, Darfurnica, 2011

It should be noted that Louis Vuitton is not the only brand depicted on Darfurnica – Chanel, Hèrmes, Paramount, Facebook, and PetroChina are also featured. Did they sue? No.

Only Louis Vuitton complained that this association damaged the company's reputation and was a violation of its industrial property rights. In the first instance, Plesner was condemned to pay 5,000 euros for each day she continued to show Darfurnica in the gallery space or online, for a total of 485,000 euros.

However, in the second instance the Court of The Hague acknowledged that the artist's use of industrial property rights within her painting was "functional and proportionate" and not aimed at a mere commercial purpose.

The Court found that the freedom of artistic expression, protected in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (which includes, according to the Court's interpretation, "offending, shocking or disturbing" through a work of art) prevailed in this case.

This concept has been included in the art. 27 of the Directive 2015/2436 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2015:

“Use of a trade mark by third parties for the purpose of artistic expression should be considered as being fair as long as it is at the same time in accordance with honest practices in industrial and commercial matters. Furthermore, this Directive should be applied in a way that ensures full respect for fundamental rights and freedoms, and in particular the freedom of expression”.

So, “freedom of artistic expression” is the keyword.

|

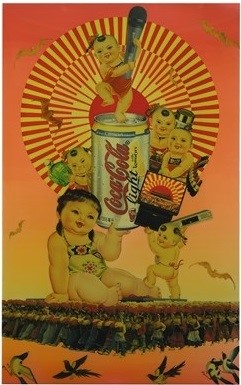

Also in China, increasing acceptance of westernized culture is a subject addressed by several of its best-known contemporary artists. For instance, the Luo Brothers (a Chinese artist trio best known for their Pop Art take on propaganda and kitsch items produced during the Cultural Revolution in China), mix the brightly colored aesthetic of popular Chinese art with icons of western consumerism, such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Sony batteries, chewing gum etc. In fact, the work of Luo Brothers, as a whole called “Welcome to the World Famous Brands”, is a parody of a well-balanced, glossy type advertisement. |

| Luo Brothers, Welcome to World Famous Brands, 2015 | |

The work of Wang Guangyi is more ambiguous about western-style consumerism. The implication in Wang Guangyi's images is that propaganda and marketing are closely connected, both trying to convey ideals that often cover less pleasant truths. A series of his works is called “Great criticism”.

Wang Guanyi, Great Criticism- Dior, Oil on Canvas, 2005 (source: Christie’s)

As far as we know, nobody addressed any complaint about the use of western brands in the works of these Chinese artists.

But as a conclusion, we may say that an overly strict interpretation of trademark law could deprive contemporary art of some of its most expressive paintings and that the judgment of counterfeiting must necessarily consider (also) artistic freedom and expression.